Justus von Liebig (1803-1873)

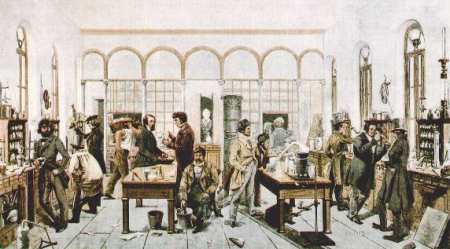

Although embroiled in professional controversies, Liebig established a large, modern chemistry laboratory that attracted numerous students. He developed unique equipment to analyze inorganic and organic substances.

Liebig restudied protein compounds (alkaloids previously discovered by the chemist Mulder), and concluded that muscular exertion by horses or humans required mainly protein, not carbohydrate and fat. Liebig's influential Animal Chemistry (1842) communicated his ideas about energy metabolism (Carpenter, 1994):

Because he so dominated chemistry, Liebig's theoretical pronouncements about the relation of dietary protein to muscular activity were generally accepted without review by other scientists until the 1850s. Guggenheim (1981) emphasizes the surprising fact that Liebig never carried out a physiological experiment or performed nitrogen balance studies on animals or humans. Liebig looked down on physiologists, believing them incapable of commenting on his theoretic calculations unless they themselves achieved his level of expertise.

By mid century, physiologist Adolf Fick (1829-1901) and chemist Johannes Wislicenus (1835-1903) challenged Liebig's dogmatic pronouncements about the role of protein in exercise. Their simple experiment measured changes in urinary nitrogen during a mountain climb. The protein that broke down could not have supplied all the energy for their hike. The result discredited Liebig's principle assertion about the role of protein metabolism in exercise. Although erroneous, Liebig's notions about protein as a primary exercise fuel worked their way into popular writings. By the turn of the 20th century, his idea that athletic prowess requires a large protein intake seemed unassailable. He lent his name to two commercial products: Liebig's Infant Food, advertised as a replacement for breast milk, and Liebig's Fleisch Extract (meat extract), which supposedly conferred special benefits to the body.

Liebig argued that consuming his extract and meat would help the body perform extra "work" to convert plant material into useful substances (Holmes, 1974; Shenstone, 1895). Even today, fitness magazines tout protein supplements for peak performance with little except anecdotal confirmation (Carpenter, 1994). Whatever the merit of Liebig's claims, debate continues, building on the metabolic studies of previous history makers W. O. Atwater (1844-1907), F. G. Benedict (1870-1957), and R. H. Chittenden (1856-1943) in the United States, and M. Rubner (1854-1932) in Germany. Liebig, a giant in his field at the time, fell prey to a common dilemma: how to capitalize on commercial efforts while maintaining academic respectability. Unfortunately for Liebig, his dogmatic pronouncements and beliefs, rather than embracing truths discovered by experimentation and verification, clouded his many important discoveries in the embryonic field of nutritional biochemistry. References Carpenter, K. J. (1994). Protein and Energy: A Study of Changing Ideas in Nutrition. London: Cambridge University Press. Gardner, E. J. (1972). History of Biology, Third edition. Minneapolis: Burgess Publishing Company. Guggenheim, K. Y. (1981). Nutrition and Nutritional Diseases. Lexington, MA: Collamore Press. Holmes, F. L. (1973). Justus von Liebig. Dictionary of Scientific Biography. Volume VII. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. Shenstone, W. A. (1895). Justus von Liebig: His Life and Work (1803-1873). New York: Macmillan. Additional Resources Rossiter, M. W. (1974). The emergence of agricultural science: Justus Liebig and the Americans, 1840-1880. Ann Arbor, MI: University Microfilms. Liebig's Chemical Letters, published by Peter Child, a lecturer in Chemistry at the University of Liimerick. Photo of Liebig's chemistry laboratory from Justus-Liebig-Museum in Giessen. Copyright ©1998 |

After studying in France with eminent scientist Gay-Lussac,

Liebig became Professor of Chemistry at the University of Giessen when

he was only 21. He dominated both organic chemistry and, after 1840,

agricultural chemistry. In later years his ideas about the proper constituents

of fertilizers were criticized because the benefits could not be substantiated.

Like other innovators, he fought with influential chemists such as Jean

Baptiste Dumas, whom he accused of plagiarism (

After studying in France with eminent scientist Gay-Lussac,

Liebig became Professor of Chemistry at the University of Giessen when

he was only 21. He dominated both organic chemistry and, after 1840,

agricultural chemistry. In later years his ideas about the proper constituents

of fertilizers were criticized because the benefits could not be substantiated.

Like other innovators, he fought with influential chemists such as Jean

Baptiste Dumas, whom he accused of plagiarism (